How can policymakers in education & training help achieve EU objectives in digital skills and jobs?

Countries around Europe are aiming to support the digital economy through building basic digital literacy in the wider population, as well as stimulating the higher level digital professional skillsets needed to create and use professional digital tools and platforms at work. In Europe, the EU institutions are working with policy makers at national and regional level to implement diverse approaches to address the shortfall. What are some of the actions that policy makers can take to help achieve the EU’s objectives in digital skills and jobs?

What are the objectives we are aiming for and why?

Digital skills are a key aspect of the digital economy. Without a sufficient talent base of digitally literate employees and ICT specialists in Europe, EU Member States risk not being able to compete in the world when it comes to the development of new products or services, or taking advantage of the productivity gains that digital tools can provide. And indeed, challenges around building basic digital literacy and specialised technical skills for working with advanced digital technologies persist, hampering the ability of European companies to compete on the global market.

The EU is also lagging behind when it comes to applying digital technologies to optimise areas of work, and the extent of this varies depending on the sector. For instance, 83% of companies in manufacturing, machinery and transportation in the European Union have taken up advanced digital technologies like robotics or AI, compared to firms in construction, where uptake stood at just 52% (European Investment Bank 2023). Yet another challenge is the urgent need to develop specialised ICT skills and a sound talent base that works for both ICT graduates and recruiters and employers.

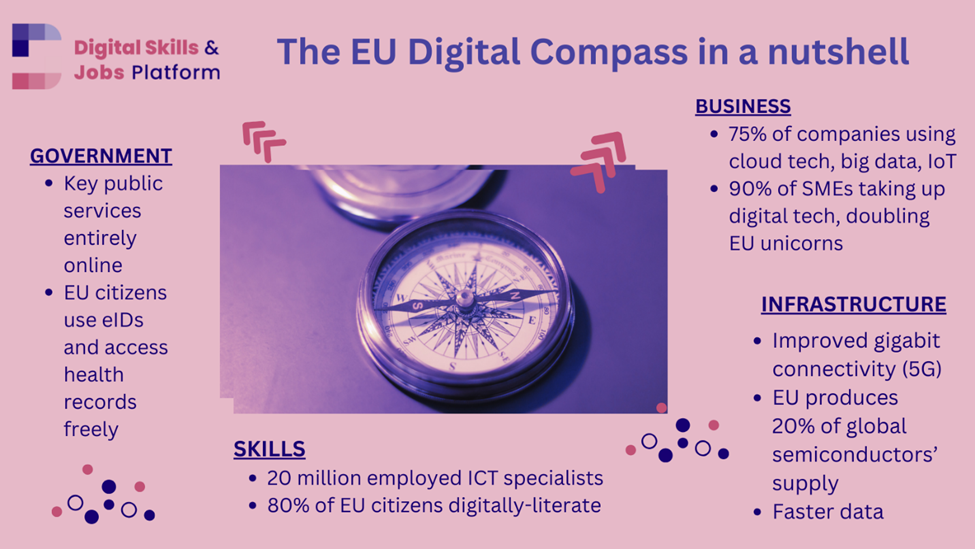

The European institutions and member states have thus taken the decision to tackle these problems collectively. The objectives of the European Union in digital skills and jobs are ambitious, as set out in the 2030 targets of the Digital Decade. The aim is to ensure at least 80% of citizens in the EU have at least basic digital skills, with 20 million employed ICT specialists with a higher level of ICT graduates and better gender balance. These targets are supported by a wider approach to digitalisation across government and the economy, as set out in the Digital Compass of the European Commission, presented in Figure 1 below.

The EU is also lagging behind when it comes to applying digital technologies to optimise areas of work, and the extent of this varies depending on the sector. For instance, 83% of companies in manufacturing, machinery and transportation in the European Union have taken up advanced digital technologies like robotics or AI, compared to firms in construction, where uptake stood at just 52% (European Investment Bank 2023). Yet another challenge is the urgent need to develop specialised ICT skills and a sound talent base that works for both ICT graduates and recruiters and employers.

The targets are challenging, as recent data from the Digital Economy and Society Index shows that “only 54% of Europeans aged between 16 -74 have at least basic digital skills.” And indeed, Eurostat counts just 9 million ICT professionals in the EU compared to the target of 20 million. But this is far from the only concern in the field. To better reflect different layers of digital performance and thereby track Member States’ progress, in 2023 the European Commission integrated DESI into the State of the Digital Decade report – an action also in line with the 2030 Digital Decade Policy Programme.

The European Union and Member States are working closely together to design and implement programs to tackle these challenges through a cycle of policy cooperation throughout the Digital Decade as shown in the figure below.

Together, the various levels of policy makers aim to make progress against Europe’s objectives in this field.

What are the challenges we face?

The challenges that education and training policy makers can address can be broken down into 4 key areas:

- Digital inclusion of all citizens

- Digital competency as part of learning

- Digital skills for employability

- Advanced digital skills for ICT professionals

Closing the digital inclusion gap once and for all

Digital inclusion of all citizens involves ensuring that every citizen in Europe has at least a basic level of digital competence. Reaching every single person in Europe is difficult for education and training policy makers, as there will always remain some, who are fearful (or sceptical) of digital technology. One survey found that as many as 72% of EU citizens fear that technology may ‘steal people’s jobs’ (Cedefop, 2018).

There is also no “one size fits all approach” to reach a multitude of citizens, especially when recognising that those most likely to be digitally excluded are also those, typically excluded for other social or economic reasons (e.g. disability, lack of knowledge of the local language, etc.). Finding ways to offer inclusive, multi-lingual education and training programs that reach the most fragile parts of the population is extremely challenging.

Another key challenge in digital inclusion relates to the gender divide, with only 17% of women in STEM studies compared to 42% of men. In IT specifically, this divide is also reflected in career aspirations. Across the EU, on average 10% of 15-year-old boys expect to work as an ICT professional, while only 1% of girls do. Societal pressures (e.g. lack of role models or support in choosing an IT career) as well as non-inclusive curricula, focused on abstract IT principles, are likely to partly explain this gap.

Core competences in an increasingly digital education

Achieving key digital competence in formal education primary and secondary education also presents its own challenges. Although there is widespread recognition among policy makers that this is important, driving the necessary changes in education institutions is challenging. Bringing in new curricula takes time, and technologies required in jobs tend to change rapidly, with the result that curricula are rapidly outdated.

Digital skills of educators are also a barrier: integrating more digital skills requires a more digitally-skilled cohort of educators, which is particularly challenging with an aging population of educators who have limited time and support for professional development. Education institutions also lack sufficient infrastructure and resources to deliver digital skills learning experiences: for instance, in primary and secondary schools, on average 30% of students have access to a personal device at school, as compared to almost of 100% of students in the US. Similarly, many European schools lack sufficient bandwidth to work online and provide rich digital learning experiences to their students.

Digital skills for the labour market: in IT, and the world of work beyond

Digital skills for employability are also challenging for education and training policy to address. Existing education and training systems, particularly at levels close to jobs (e.g. higher education and vocational training) tend to be discipline specific and slow to integrate cross-discipline approaches integrating IT that are needed for digital skills for employability. Technical and vocational training systems have often been neglected from an investment standpoint (UNESCO, 2022), and have similar needs to primary and secondary schools in terms of increasing student device access and appropriate levels of connectivity.

In the European Union, higher education institutions have been effective at providing advanced computer science (CS) education. However, there is a disconnect between traditional academic CS and high-level IT professional skills. For instance, although employers are heavy users of cloud technologies, these are often of relatively low importance in CS degrees (IEEE, 2015). EU academic institutions have also been slower to move to specialized courses in emerging advanced technologies: for instance, in AI more specialised Master’s degree courses exist in the US and UK compared to the EU. Similarly, Anglo-Saxon universities are often more willing to create integrated courses with industry partners that combine both academic learning and industry-specific knowledge, which helps students segue more quickly into careers post-university. European academia is traditionally more sceptical of partnering with industry, which has been a barrier to developing this type of approach.

Another key issue in higher education is the attractiveness of CS and IT as a subject area. Although there has been growth in the number of students entering CS degrees (add ref here), the relative number of students in CS remains lower than many other disciplines. CS students are also a homogenous group, with few female students nor students from minority backgrounds taking up the subject.

Though the challenges are multi-faceted, education and training policy makers are in a unique position to be able to address them. The next section of this paper moves on to outline the opportunities that education and training policy makers have to influence change.

What are the opportunities for education and training policy makers to address these challenges?

For all of the above areas of digital skills, there are numerous positive models and approaches to be explored. Policy makers need to ensure that they are resourced, funded and remain a political priority to impact digital skills in the EU.

Let us go back a bit and look at digital inclusion: and how we can get it to actually reach all of Europe’s citizens. When it comes to initiatives on digital inclusion, policy makers in education and training have various levers they can activate. Focusing on the community is a key approach here: and this goes from providing grants for projects and activities to setting up actual physical spaces, like in the case of Molengeek (a non-profit organisation dedicated to offering training to the refugee and migrant community in one of the most deprived neighbourhoods in Brussels). Molengeek offers training and coaching to segments of the population typically excluded by other initiatives, and supports them in acquiring basic digital literacy and more advanced skills to run a business or a start-up. In Molengeek’s case, public funding is combined with private investment.

But this is far from the only example in Europe targeting marginalised groups. REDI School operates in several EU countries and provides training to people from a migrant background, with a special focus on women. Citilab, just outside the city of Barcelona is another a good example of a physical space in the form of a citizen lab for social and technological innovation. The community organisation offers a wide variety of trainings for citizens and schools, as well as building local innovation projects together.

Another avenue, where policy makers can offer support is helping libraries transform into true digital competence hubs. In today’s increasingly digital world, libraries have become a key access point for citizens looking to upgrade their digital competences, and up-skill further. Examples of libraries offering access to digital skills initiatives are everywhere in Europe, and funding for this has been secured by National Recovery and Resilience Plans of EU Member States. In Romania, funding from the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will go towards supporting more than 100 libraries in improving access to digital literacy opportunities and helping citizens acquire future-proof skills.

Policy makers can also support libraries in becoming digital competence hubs; they are increasingly offering access to citizens and others to develop their digital skills. For instance, in Romania, as part of the national RRF plan 105 libraries will be funded to develop digital literacy, communication, media literacy and many other related skills . They can also partner with non-profits to do so; for instance, Coderdojo offers volunteer-led coding clubs in libraries across many countries.

Educator skills are critical to enable improvement in digital competence in primary and secondary schools. Education policy makers can address this by requiring a certain amount of digital professional development per year, reducing the cost to access PD and including digital skills within required teacher competency standards. Decision makers can also encourage public private partnerships in the area – many large technology companies offer free online training for teachers, to use the tools that their schools have purchased. Equally, as leaders procure new technology, they should require professional development as part of the purchasing process to avoid a disconnect between what is provided to schools, and the training that educators receive.

Similarly, although many member states have made significant progress in curriculum change to foster increased digital skills, others still have work to do. There are numerous approaches to do this, from integrating a digital competence in competence-based curricula, or to consider IT and computer science on a similar footing to the traditional sciences. Policy makers need to continue to monitor the impact of curriculum change and understand what really makes the difference for students.

Industry partnerships are also a useful way to bring more digital competence into schools. EU Code Week, an annual campaign of the Commission, has been a good example of this with companies cooperating at EU and national level to support schools in bringing more opportunities to learn computer science into schools.

Digital skills for employability

For digital skills for employability, traditional training has often been replaced by the bootcamp model to increase the digital skills of non-technical people to be able to employed in technical roles. However, many people struggle to get recognition or employment despite developing these skills, so government leaders need to find ways to quality check and recognise the value of non-traditional learning pathways.

Certification in digital skills can also provide a solution: industry-focused certifications provided by the large technology companies can be useful to acquire jobs in their ecosystems, while agnostic certifications enable people to prove their skills across multiple technology platforms. Again, these should be recognised with official training credits (e.g. ECTS) to underscore the value of these qualifications on the market and for future academic study.

Digital skills development in technical and vocational training also needs to be improved; according to UNESCO (2022), the main opportunity here is to focus much more deeply on training programs for TVET educators, using a combination of traditional professional development, networks for professional learning and multi-stakeholder partnerships.

High level IT professional skills

Although joint industry-academia degrees and study programs are not yet common across Europe, they are being actively promoted by the DIGITALEUROPE program which is encouraging academic-industry partnerships to co-develop degrees in topics like AI and cybersecurity. Some universities in Europe are also engaged in such partnerships independently. For instance, the Università Degli Studi Di Napoli Federico II has partnered with Apple to launch a Developer Academy, where young people engage in challenge based learning to learn design, business and technology and eventually start to build their own start up. SKEMA business school in France has worked with Microsoft since 2016 to integrate high level skills into the curriculum they provide for business and HR courses.

The EU is funding and promoting more awareness of higher-level IT professional courses to students particularly in in-demand areas, to make it easier to find and attend courses across the EU. For instance, ENISA’s CyberHEAD database indexes Cybersecurity courses available in the EU and EFTA countries.

Bringing in more non-traditional candidates into computer science degrees is a key part of the effort. Governments can support awareness-raising campaigns and career support for girls to encourage them to consider CS studies, potentially in partnership with industry. For example, UNESCO organised AI hackathons for girls close to choosing their degrees, to teach them about computer science and the opportunities it offers . Governments can also offer financial support to relevant stakeholders and associations: a good example is the EUGAIN project led by Informatics Europe, an association representing the IT research and academic community. EUGAIN supported further collaborative work and exchange among academics pro-actively working to improve gender participation in CS in their countries.

Leaders might also consider grant schemes to encourage workforce development partners to address higher level digital skills. These organisations – not common in all member states – interview candidates and put the most promising people through a skilling program mixing digital and non-digital skill sets. They then go on to place candidates with companies seeking digital skill sets, who have signed up to take on non-traditional profiles with the right skill set. Some European organisations such as Adecco and Akkodis are already engaged in these types of programs and could be emulated in other parts of Europe.

Endnote

Although the challenges to digital skills in Europe are wide-ranging, there are also plenty of solutions already implemented at EU and member state level that can be scaled up or learned from to drive an improvement in the level of digital skills at all levels of education. Policy makers need to proactively learn from each other across countries, and build joint efforts to address the issue. In addition to implementing practical solutions, it is critical that policy makers advocate for an ongoing focus on digital skills from a political perspective, so that it continues to receive the attention and resourcing needed to achieve the goals of 2030.

About the author

Over the last 20 years, Alexa Joyce has worked with governments in more than 100 countries across the world in the area of digital transformation. She has been active in education technology for more than 20 years, with half of her career in big tech companies and the other half – in the public sector. Alexa has worked for several leading international education organisations: European Schoolnet (the network of 34 Ministries of Education in Europe), UNESCO and the OECD. She has also been an advisor on numerous boards, including the European Centre for Women and Technology, ALL DIGITAL – a European network for digital inclusion, University College London’s EDUCATE incubator for ed-tech start-ups and the Institute for Ethical AI in Education.