Digitalising the 4th Estate: exploring media’s changing role as an information channel & its impact on public discourse, opinion (deep-dive)

How often do you sit around a table to discuss small happenings in your town, the results of a national election or major world events? Our shared reflection on shared events has reduced significantly over the past decades, in favour of personalised experiences of digital, quick news feeds, tailored by sophisticated algorithms to individual preferences. In this Digital Brief, we dive deeper into how these changes in our news consumption of the Fourth Estate effect our notions of opinion and fact, our abilities to think critically and how new constellations of community can offer respite. We focus on the essential role of the Fourth Estate in our democracies, as shared spaces for meaning-making, the consequences of their decline, and how to bring them back to life in new forms.

Subtitle

An exploration of the changing role of media as the primary channel for information distribution and the impact on public discourse and opinion. This paper takes a historical perspective on the shift from of the Fourth Estate in centralised media to decentralised media. It critically examines notions of “gatekeepers” and “shared spaces” to identify how a crisis of critical thinking has emerged.

Keywords

Information, community, media literacy, critical thinking, media.

Why should we care? Media as we know it

Our news consumption habits have drastically changed over the last decades, transformed by the rapid digitalisation of media (European Parliament et al., 2023). The Media and News Survey 2023 on the media habits of Europeans indicated that more than 30% of people primarily get their news from social media, next to radio and TV. This has a profound effect on the ability of younger generations to relate and interact with news. Just half of EU citizens indicate they trust public TV and radio most as a primary news source. The generational gap can be noticed even more if we look at individual preferences: older people tend to go for websites and TV channels of trusted sources, while younger people choose to access their preferred sources of news via social media.

All this has led to a shift in public perception of journalism – with feelings ranging from apathy to traditional journalism practices, to a complete decline in people’s trust toward mainstream media. This is exacerbated by the perception of broadcast media companies as subjected to big technology corporations and the blurring of commercial and journalistic content.

Let’s dive into the consequences of these trends - exploring their origins too.

The essential Fourth Estate in democratic societies

Public broadcasters and media fall under the “Fourth Estate”, a concept referring to media's crucial role as the 4th pillar of society, standing alongside the executive power, judiciary power, and legislative power in a democratic society. Zooming in on the role of media in today’s society, the Fourth Estate’s fundamental purpose is to offer information, insights, control, and scrutiny to citizens when it comes to governmental decisions and actions.

Media perspectives

This involves investigating and communicating news, i.e. verified, undisputed facts and events to raise awareness both to the general public and the regional, national and international policy makers. It also involves the unearthing of relevant trends and patterns in society to identify relevant themes for the present and the future. Finally, it also provides a point of society-wide reflection on ongoing events, to contextualise the importance of these events, beyond their momentary relevance in a small scope. Through these activities, it can also give insight into general public opinion and provide visibility of public sentiment to all levels of government. To fulfil this complicated role, traditional media build on various professional standards, individual and team-level norms in conduct, and tested methodologies such as news reporting and journalistic editing, to ensure the factual correctness of what is being reported. In democratic societies, the role of the Fourth Estate is particularly vital, as media insights into a country's or region's priorities and needs lay the foundation for many critical decisions from local to global level.

People depend on the Fourth Estate to get access to trustworthy news and information, to inform and exercise their democratic rights and civic duties Therefore, news media in broadcast and print forms has a crucial role to pay in ensuring the healthy functioning of democratic societies.

Journalism is a team sport: a complex organisation with diversified tasks and roles

With this crucial societal perspective of traditional media in mind, we turn our attention to the complex yet indispensable discipline of print and broadcast journalism at the heart of the Fourth Estate. A journalist is a trained professional equipped to distinguish fact from opinion, consolidate and verify events, investigate matters thoroughly, and report accurately (Guo & Volz, 2021). The key competence of a journalist is that of (News) Judgement, which can be defined as the “cognitive acts of understanding what matters: what is most important or most interesting”(Clark, 2014). In other words, they continuously view and analyse events to decide and judge what events matter, and in which way.

Although all journalists need to adhere to methodological standards and norms, they can also specialise in terms of knowledge or content (e.g. on specific countries (e.g. China, India) regions (e.g. Middle East), and methods (e.g investigative journalism, photo journalism, data journalism). Moreover, journalists can also voice informed opinions and become public opinion makers and shapers but this is highly labelled and controlled by the ethical standards of the profession. The paramount aim remains clearly distinguishing between opinion and verified facts.

Moreover, journalism is a team sport, where different tasks from the news gathering to the reporting and analysis stage are specialised and tuned to confirm accuracy and fairness at each stage (e.g. core principles of in the mission of the Ethical Journalism Centre). The myriad roles of editors, subeditors, correspondents, reporters, etc. scrutinise the way a story is identified and communicated to achieve this goal of verified, trustworthy news. Each member of a broadcast or print journalistic team carries a specific function in this process.

What are the consequences of digitalising the Fourth estate?

The invention of the internet, the World Wide Web and social media has brought about significant changes to journalistic practice. These technologies (in theory) essentially make a global media channel available to every single person on planet Earth, who can decide freely what they want to use this channel for. The success of this is visible in the abundance of content creation and connections, visible from the initial stages of the Web, through original webpages, over the blogosphere to the current social media ecosystems.

In this technology-supported world, every person (who wants to) can be a content creator, with the freedom to create specific material for their audience, on whatever topic they want, and via whichever media they prefer. They can be experts in their topic, discipline and field, or develop this knowledge more deeply through the content creating activities themselves.

On a superficial level, this jars with the activities of traditional journalism, as they both focus on creating media content for their audience. The digitalisation of the Fourth Estate has brought about several significant shifts in the media landscape.

On production of media, we have witnessed a transition from centralised to decentralised media, fundamentally altering the way information is created and disseminated. The public's role has transformed from being mere information receivers to active information publishers, leading to increased participation in media creation. Digitisation causes opposing drivers, where there is more questioning of traditional media producers, on their news judgment. More individual and group voices can get attention, addressing topics that they might deem newsworthy but that fall through the net of traditional media. People can also have access to more authentic lived experiences and can connect on a personal level with strangers across the world. However, this widened media production also goes hand in hand with less scrutiny of the created media and less context to created content. Private individuals and groups are not bound by journalistic professional ethics, blurring the lines between sharing and broadcasting verified facts and opinions.

On the consumption of media, digitalisation of the media landscape has created more personalised access to news, where everyone can follow news through their preferred media (print, video, online news, etc.). Moreover, in social media feeds, journalistic media and non-journalistic media appear side-by-side, on equal footing. They give the impression of more possible direct interaction with the content creators, if these interactions are valued and managed. However, most importantly, democratisation of media creation has resulted in a fragmentation of the single, central shared public space of traditional media into a multitude of shared spaces, organized around specific themes, people, and interests. It has gradually positioned (online) (topic/theme-based) community above general public society in the experience of individual citizens. Ultimately, these shifts profoundly affect public life, influencing political discourse, social movements, and collective understanding.

Towards an illusion of connectedness in public debate

Yet another significant consequence of the digital transformation is increased levels of isolation in democratic societies. Although people have access to more authentic experiences, from virtually all corners of the world, and can interact with one another directly, they still do not feel connected on personal levels – and engagement is limited to curated digital bubbles rather than diverse real-world encounters (Turkle, 2011). In effect, this can also lead to isolation from one's community in the physical world, as shared physical experiences diminish in favor of niche online interactions. Finally, it can also result in isolation from the region where one lives, as digital connections transcend geographical boundaries, potentially diminishing engagement with local issues and people. As increasing numbers of people engage with political content online (Newman et al., 2025; Newman, 2025), this can create the illusion of connectedness and democratic engagement online, without real participation in the real world.

In search of real shared spaces

Shared spaces are vital because they create shared experiences. These shared experiences, in turn, foster points of connection among individuals who might otherwise be strangers or unknown to each other. Think of major world events: people often recall where they were and what they were doing, creating a collective memory and shared understanding. The COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, was a globally shared event that generated a widespread sense of empathy and common ground.

The value of a shared experience in forging connections cannot be overstated. Historically, lines of distinction between people often followed geographical and temporal delineations, such as nationhood, city, or common time. However, in the digital age, lines of distinction increasingly follow interest and shared digital spaces. Individuals may belong to various online communities where they share commonalities with others, but little else. This phenomenon, where people connect only on one specific thing, can unfortunately increase alienation in other aspects of their lives.

Media as powerful connecting mechanisms to create shared experiences and shared spaces

In and of themselves, media are powerful societal artefacts that can foster the creation of a shared space. This is very clear in entertainment: think of when you watch a movie together with a friend, or share a Spotify list in a family group. Media have the ability to orchestrate an immediate emotional connection with the created content, that can develop a connection between the people consuming the media. Similar situations can be observed in education, where the use of media is prolific to engage pupils and students with learning material. This also creates shared experiences that can support or hinder further learning.

When it comes to news, media again can be very powerful in capturing the engagement of listeners, viewers and readers. However, there is an added criterium in news, as – as mentioned in the paragraphs above - this content is distinguished from other content by its grounding in verifiable fact, established by journalistic trained professionals.

These gatekeepers of news are crucial for their ability to use validated methods to distinguish fact from fiction and news from opinion. They are responsible for verifying their sources and positioning themselves as authoritative and accountable voices, meaning their work can be questioned and judged. This commitment to verifiability, accountability, and authority is essential. Recognising this, the EU has introduced several interventions on the role of media, disinformation and the role of influencers in disseminating information.

The European Media Freedom Act – in full application from August 2025 - is aimed at protecting editorial independence and journalistic sources, by ensuring governance instruments and sustained funding. The Act also ensures the creation of a new independent European Board for Media Services that oversees application of the EU media law framework. The EU Audiovisual Media Services Directive unifies and coordinates the governance of national legislation on all audiovisual media – both traditional and on-demand services. In 2024, the European Audiovisual Observatory released a study on social media influencers in European and national law (European Audiovisual Observatory, 2024). This study elucidates the concept of a “influencer” in the 27 EU Member States’ legal frameworks and sets out the national laws that govern their role in society. It also points to a number of professional development programmes in certain Member States aimed at influencers.

Critical thinking in decline

The fact that consumption of media puts traditional and wider social media on an equal footing for all, puts the onus on the reader, listener and viewer to be more critical users of media. To support European citizens, the European commission invests in legislation and awareness-raising, support, and training on critical thinking.

Recognising the importance of media literacy, the European Parliament has identified it as a key skill for democratic participation (European Parliament, 2025). The European Digital Media Observatory maps out national and regional initiatives on media literacy and provides guidelines for fostering media literacy by raising the standards of Media Literacy initiatives. They also offer monthly fact checking briefs (EDMO Fact-Checking Briefs) to counter ongoing disinformation actions, and monthly digests (EDMO Media Literacy Digests) to highlight actions building media literacy skills and competences. These initiatives build on long-standing practices in news consumption in Europe (Newman et al. 2025), such as sustained children and youth access to quality news programmes in their own language through public broadcasters or the support to European teachers on engaging with pupils on news consumption and providing context through various national initiatives and resources (EDMO, 2025). They are also complemented by group-specific strategies such as the EU Youth Strategy, in which children and youth are informed and increasingly participate in democratic process, making them informed decision makers (European Union, 2018), and the Better Internet for Kids (BIK+) Strategy, which aims to ensure young people and children can safely navigate online spaces and fosters the development of critical thinking for young age groups.

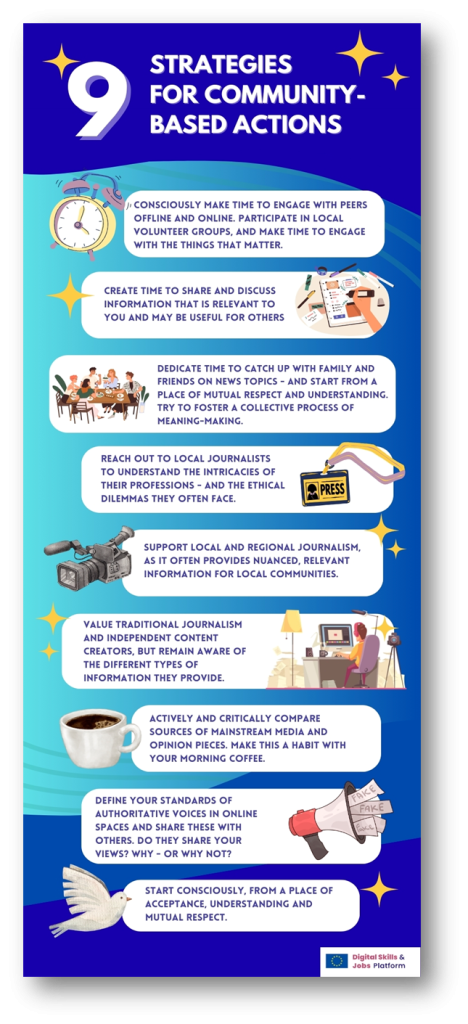

Revalue Community as a space of meaning-making

Apart from these formal strategies, there are many things that ordinary citizens like you and me can do to ensure that we reappraise the role of the Fourth Estate. This can happen through revaluing Community as a space for connection and collective meaning-making. Various individual and group strategies can be employed to develop this Community again, as illustrated in the infographic below.

These strategies address three central challenges.

The first challenge concerns viewing media consumption as a highly individual activity. This is in many ways an undesired consequence of the digitisation of media and lies at the foundation of many societal issues. Consciously breaking through this assumption, by positioning media consumption as a shared activity, can reinstate the strength of media as a community builder.

The second challenge concerns the nature of current engagement with news and content, which happens mostly online, influenced by algorithms and filter bubbles, in superficial dialogue with largely unknown and unfamiliar people. Consciously repositioning news as something to be engaged with in dialogue with close contacts and known acquaintances, will break through the current barriers and allow for safe spaces to emerge where difficult subjects can be discussed, and deep collective thought can precede opinion formation and civic engagement.

The third challenge concerns the often-unarticulated concepts of authority and expertise and how these concepts influence connecting with experts, journalists and content creators online. By engaging with more awareness with news and content, i.e. questioning why media is created, why a message is shared, how a message is shared, and what the goal is of media production, will allow to build a more balanced view on the shared content. Essential parts of this action are prioritising quality of engagement with news and content over speed and quantity of engagement, understanding and valuing the profession of journalism and expertise building, actively valuing the difference between fact and opinion, and building understanding of media in conversation with others.

Confronting these challenges with small daily conscious steps will rebuild our communities, our society and resilience.

Below is a list of strategies.

- Consciously make time to engage with peers offline and online. Participate in local volunteer groups, and make time to engage about small and big things that matter.

- Create time for sharing and discussing information that is relevant for you and may be relevant for others too.

- Dedicate time for conversation with friends and family, on news topics, starting from mutual respect and understanding. Foster a collective process of meaning-making.

- Reach out to local journalists to understand the intricacies of their profession

- Support local and regional journalism, as it often provides nuanced and relevant information for local communities.

- Value traditional journalism and individual independent content creators, but remain aware of the significantly different types of information they provide.

- Actively and critically compare sources, of mainstream media and opinion pieces as a habit.

- Define your standards of authoritative voices in online spaces, and share these with others. Do they share your views? Why or why not?

- Start consciously from a space of acceptance, understanding and mutual respect

Further reading

View the full paper, together with its references, in PDF here. The infographic can be found on this link.

Author's biography

Dr. Kamakshi Rajagopal is an interdisciplinary researcher and freelance consultant in educational design and technology, with extensive experience in networked learning and social learning formats, supported by innovative technologies. She holds a Masters in Linguistics (2003) and Artificial Intelligence (2004) from KU Leuven (BE). She completed her doctoral research at the Open Universiteit (NL) in 2013, investigating personal learning networks and their value for continuous professional development. Her current research is on studying the complexity of learning environments and more specifically on how teachers and learners can be supported in dealing with this complexity. Dr. Rajagopal has developed multiple (nationally-funded and European) collaborative research projects in primary, secondary and higher education with partners from the public sector, industry and civil society. Key themes in her work include teaching as design, data-driven decision-making, and teaching in media-supported learning environments. Since 2023, she has been working as a consultant in Learning and Development, supporting private companies and other organisations in aligning their technology products with their business ambitions. She is also the founder of SAMAM, a community-driven organisation supporting teachers with data-driven insights into their profession.